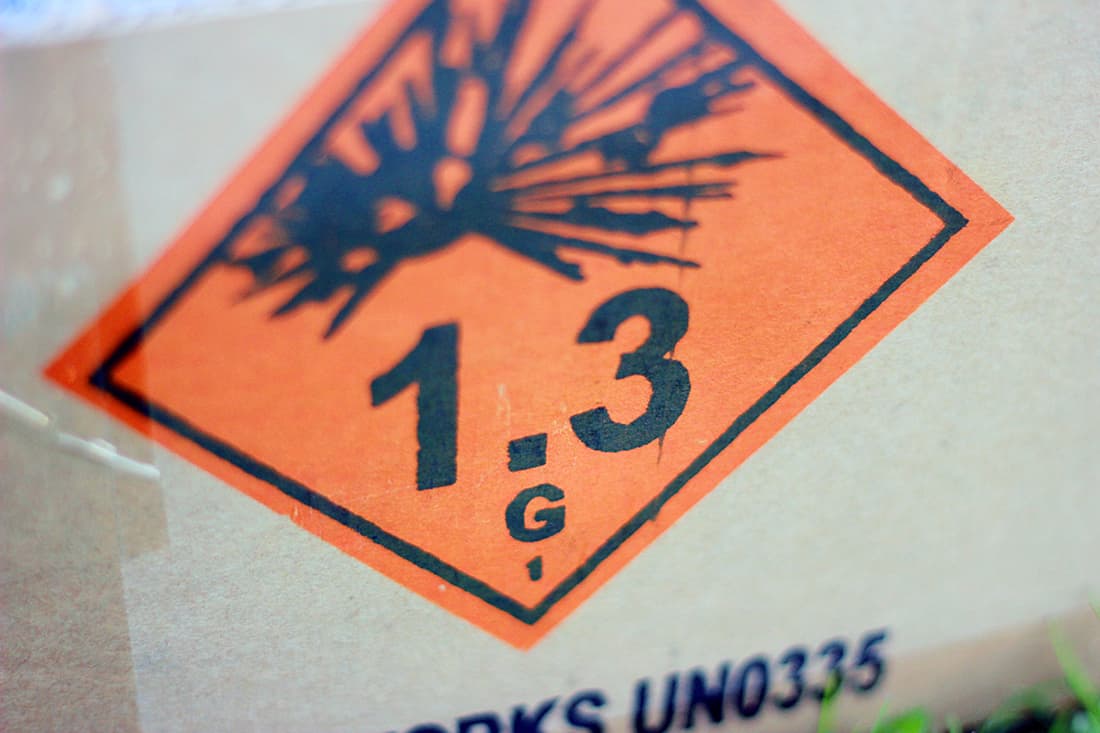

1.3G or 1.4G Fireworks?

The difference between 1.3G and 1.4G fireworks and whether it matters.

When shopping for fireworks these days you’ll quickly come across the somewhat ambiguous terms of 1.3G and 1.4G. Some retailers also make a point of emphasising their 1.3G fireworks as being more powerful. But what exactly do these terms mean? Let’s delve into it.

Key information

- The classifications of 1.3G and 1.4G denote the “hazard” of the firework for storage purposes.

- 1.3G is more hazardous than 1.4G.

- 1.3G is therefore generally seen as more the powerful consumer firework.

- Not to be confused with the category of the firework (Category F2 or Category F3).

- 1.3G fireworks are subject to stricter storage and transport restrictions.

- 1.3G fireworks can be encased in wire mesh packaging called pyromesh by their manufacturers to make them 1.4G.

The basics

Quite separate from their safety category (F2 or F3), fireworks are also given a hazard category, which is 1.3G or 1.4G. This determines under UK law how many fireworks can be legally stored in one place and for how long. The lower number, 1.3G fireworks, are the more hazardous. This hazard category is printed on the outside of the firework’s box.

By “hazardous” I do not mean that 1.3G fireworks are more dangerous to handle, just that any type of explosive product on sale has to be classified depending on the risk it poses, for example in a fire. This risk then determines, by law, how much of that product you can store in one place.

Note: For the purposes of making this a beginner’s guide I have over-simplified the classification and hazard types of fireworks. For a more detailed and technically correct guide, see the Firework Classifications article.

As a consumer you wouldn’t ordinarily have to worry too much about this, unless you are buying a very large amount of fireworks or intending to store them for a long time before your display, in which case you would need to observe the laws relating to the maximum amount you can store and the time limits on this storage.

However, more and more firework retailers are making reference in their sales literature to the 1.3G and 1.4G classification in particular pushing 1.3G as a more powerful firework, or emphasising “1.3G effects” as a selling point.

Most consumer fireworks on sale are 1.4G because greater numbers of these can be stored by the retailer (1.3G storage is so restrictive that retailers either need a store with sufficient separation distance from neighbours, or to fulfil orders for 1.3G on demand, which can be time consuming and expensive). Many firework couriers will also only take 1.4G and not 1.3G as there is a risk in peak periods that too many fireworks will be in their depots.

As a result of these restrictions you will almost never see 1.3G fireworks on sale in supermarkets and similar seasonal sellers, rather, they are restricted to specialist firework shops which have the correct storage in place.

What makes a firework 1.3G rather than 1.4G?

Surprisingly it is not the overall amount of gunpowder (known as the NEC – Net Explosive Content) in a firework that has a bearing with most firework types but rather the amount of flash powder. This is a more explosive form of gunpowder and is used as a bursting charge. Fireworks with greater than a certain amount of flash powder have to be classified as 1.3G. An example would be with cakes, that if more than 5% of the weight of the tube was flash powder then the cake would become 1.3G.

Flash powder is the ingredient in a firework that helps to create a bigger – and usually louder – explosion when the main effect of the firework goes off. There are other non-gunpowder formulations too and they are treated for classification purposes as if they were flash powder.

Are 1.3G fireworks better than 1.4G fireworks?

Retailers are generally correct in pointing out that their 1.3G fireworks have a higher explosive power than 1.4G fireworks.

However whether this greater power equates to a better firework is entirely down to the design of the firework and to some extent, subjective opinion. In recent years, 1.4G cakes and barrages have improved to the point that the classification really doesn’t matter unless you are specifically after the most powerful barrages available.

But one type of firework where this classification makes a huge difference is rockets. This is because the restrictions on 1.4G rockets are quite severe and without sufficient flash powder, 1.4G rocket bursts can be quite tame. This is why many smaller 1.4G rockets only “pop” when they go off. On the other hand, 1.3G rockets have a much bigger bang. Even smaller 1.3G rockets (right down to £5 packs) can outperform bigger and more expensive 1.4G rockets.

In technical terms, 1.4G F2 rockets cannot contain any flash powder and total NEC must be less than 20g. That’s pretty restrictive. 1.3G rockets can go up to 200g NEC with the F3 classification and contain flash powder or equivalent formulations to give that “bigger bang”.

The best way I can summarise this is as follows:

- 1.4G cakes and barrages are rarely “underpowered” compared to 1.3G cakes; use retailer video clips to inform your buying choices rather than just the 1.3G or 1.4G classification. They are more than adequate for back garden displays.

- 1.3G rockets are substantially better than 1.4G rockets. The latter tend to just “pop”.

The anomaly: 1.3G fireworks made into 1.4G fireworks

As if all of this wasn’t too much to take in, there’s also the case of 1.3G fireworks made into 1.4G fireworks.

To understand why manufacturers would even do this, consider that 1.4G as the less hazardous classification allows for significantly less storage restrictions and easier transport. So if a 1.3G firework can be somehow classified as a 1.4G firework it has a lot of advantages.

This can be achieved with some nifty packaging which is known in firework circles as pyromesh. Essentially the 1.3G firework is encased in a removable wire mesh cage inside the outer cardboard box. This has the effect, in case of fire for example, of helping to contain the explosion thus making the firework less hazardous and therefore fall within the scope of 1.4G.

So a 1.3G firework in pyromesh would have 1.4G on the outer box since, whilst it is in the mesh, this is its classification and it can be treated as a 1.4G firework for the purposes of transport and storage.

Some retailers then promote a mix of 1.4G and 1.3G fireworks although all of their 1.3G fireworks might be in pyromesh and are technically 1.4G. In that case the emphasis on 1.3G is a sales thing to highlight the bigger performing items.

Some retailers who sell 1.3G do so with fireworks which are not pyromeshed and therefore are classified, and treated as, 1.3G fireworks.

And some retailers have a mix of both.

In summary: Does it matter?

If you’re walking into a fireworks shop on November 5th and buying fireworks to let off that night, then the classification doesn’t really matter and you should base your buying choices on the retailer’s video clips and descriptions. You’ll know, from the above, that 1.3G items (whether pyromeshed or not) could be more powerful especially with rockets.

If you’re buying fireworks for a future display, say several weeks or months away, then the classification of your fireworks could make an important difference depending on how many you are buying and how long you want to store them for; be aware that restrictions on 1.3G fireworks (that’s actual 1.3G fireworks, not 1.3G in pyromesh which are now 1.4G and treated as 1.4G) are much tighter. See my article on fireworks storage for further help.

One thing that is important: Pyromesh can be a pain to remove, so allow yourself plenty of time. My article That Pesky Pyromesh has some useful advice on removing it.